Burned Homes, Broken Values: How California’s Tax Laws Are Blinding Us to Fire Risk

California’s legacy tax laws are making it impossible to truly measure the cost of wildfire destruction

As a housing data specialist, I’ve been following the recent California wildfires with a heavy heart.

Like many, I’ve been worried about the families displaced, the homes lost, and the communities forever changed. But alongside that very human concern, I found myself returning to a different kind of question — one rooted in numbers, models, and the real cost of catastrophe.

There are plenty of articles that have damage numbers already:

But those figures represent a fraction of the total damage and economic loss in the L.A. region, which AccuWeather estimated to be somewhere between $250 billion and $275 billion.

AccuWeather's estimate accounted for not only the destruction and damage of homes and businesses, but also various other factors, including damage to utilities and infrastructure, the long-term cost of rebuilding, cleanup and recovery costs, emergency shelter expenses, long-term health care costs, lost wages, and housing displacement.

The spread in the estimates caught my attention. Why are the estimates so broad? What’s missing from the models? And how do we actually quantify the destruction when the data we rely on — especially property tax assessments — might be wildly inaccurate?

I decided to look into it myself. And discovered a complete mess.

Tax Assessed Values Dataset

I’ve always known that California’s property tax system was... tricky.

Between Proposition 13’s cap on annual assessment increases and the patchwork of reassessment triggers, it’s long been understood that assessed values often lag far behind market realities. But until I started digging into the data myself, I didn’t realize just how extreme the disconnect could be.

I pulled the official latest LA County Assessor Parcel dataset, which is openly available and contains LA County tax-assessed values for 2.4 million parcels.

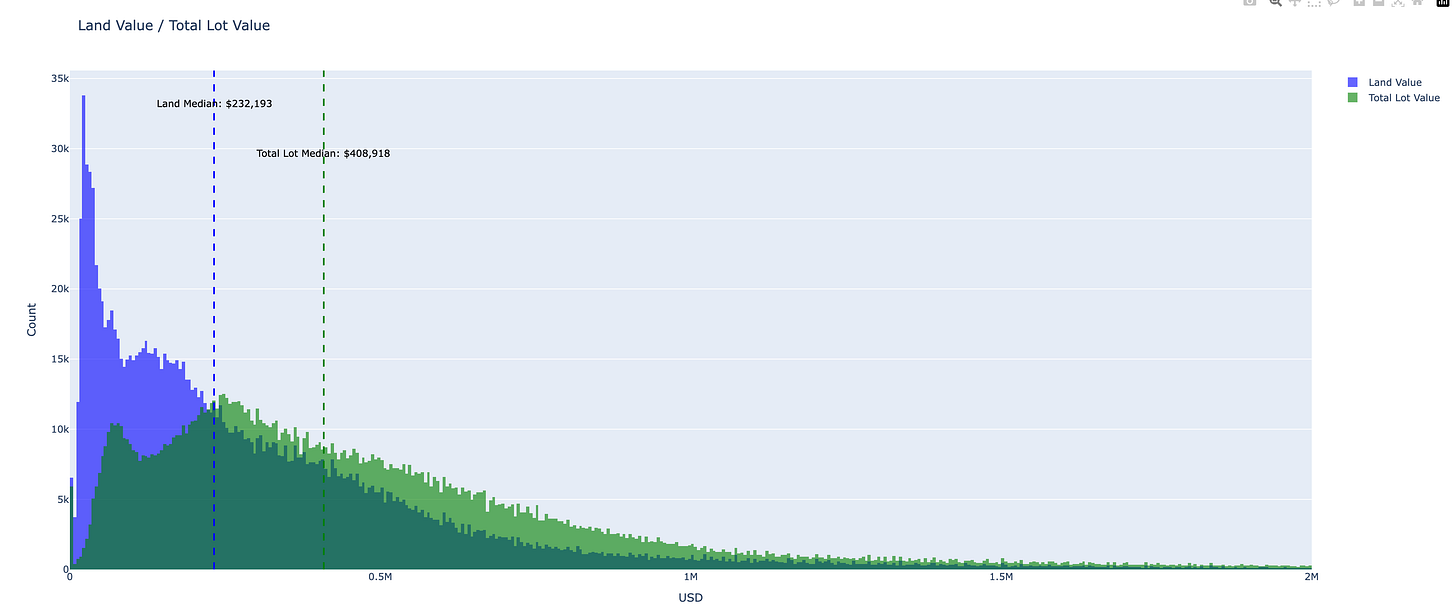

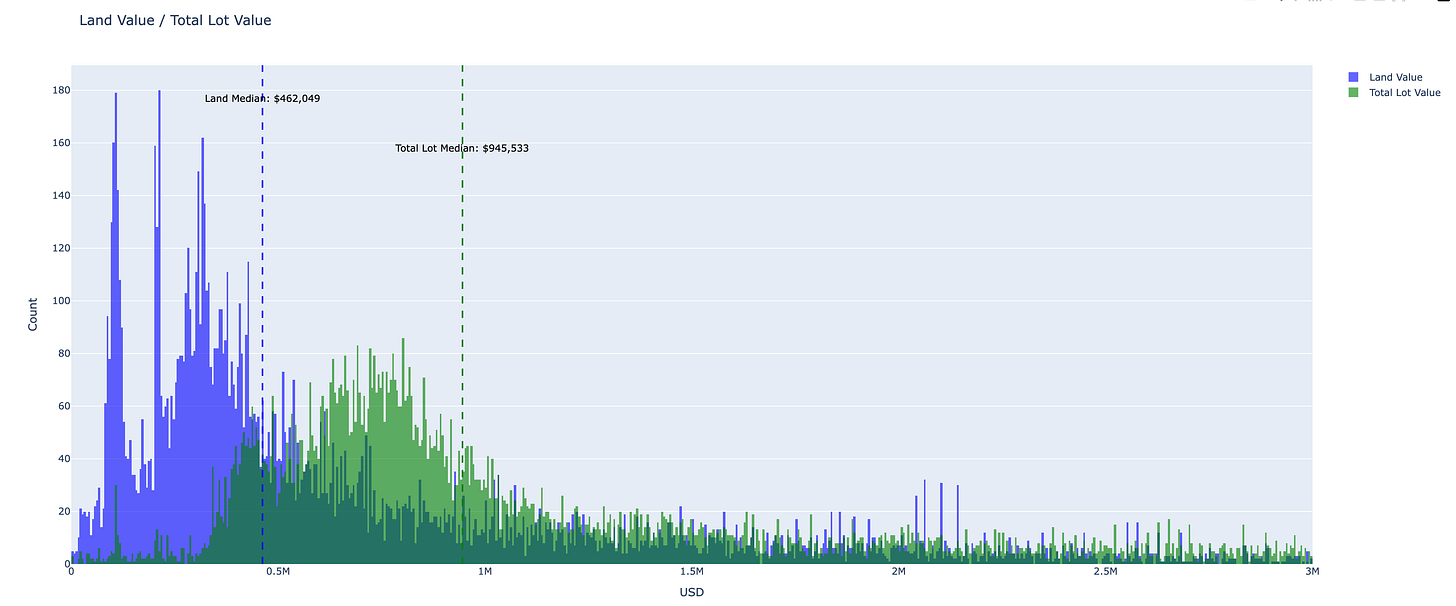

Tax assessments were published for 2 roll years - 2021 and 2022. For this analysis I’ll be using just 2022 values, which are somewhat deprecated already in 2025, but more recent data is not published yet. I’ll also be using just single family residencies to simplify the analysis.

While looking through the LA County housing stock as a whole the numbers immediately did not make much sense to me:

As measured the median Improvement value is just $151.463, while the median land value is higher at $232.193. My immediate reaction was “that can’t be true”.

When looking at the total lot median, the median value, which is “land value combined with improvement value”, it is just $408.918.

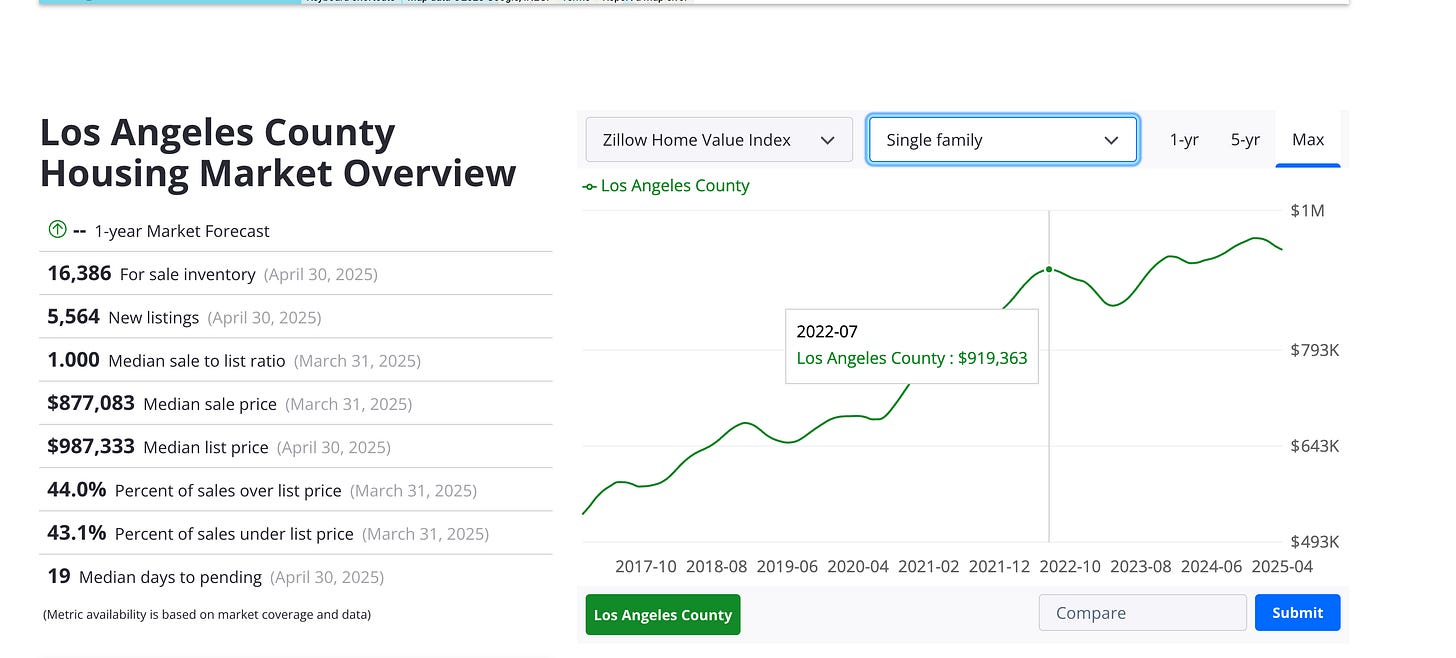

Zillow Single Family index reports a value of $919.363, which is 2.2 times higher than the median assessed value of a typical house.

Ok, setting this observation aside, let’s look at the fire perimeters and properties that were affected by the recent fires.

Fire Perimeters and Tax Assessed Values

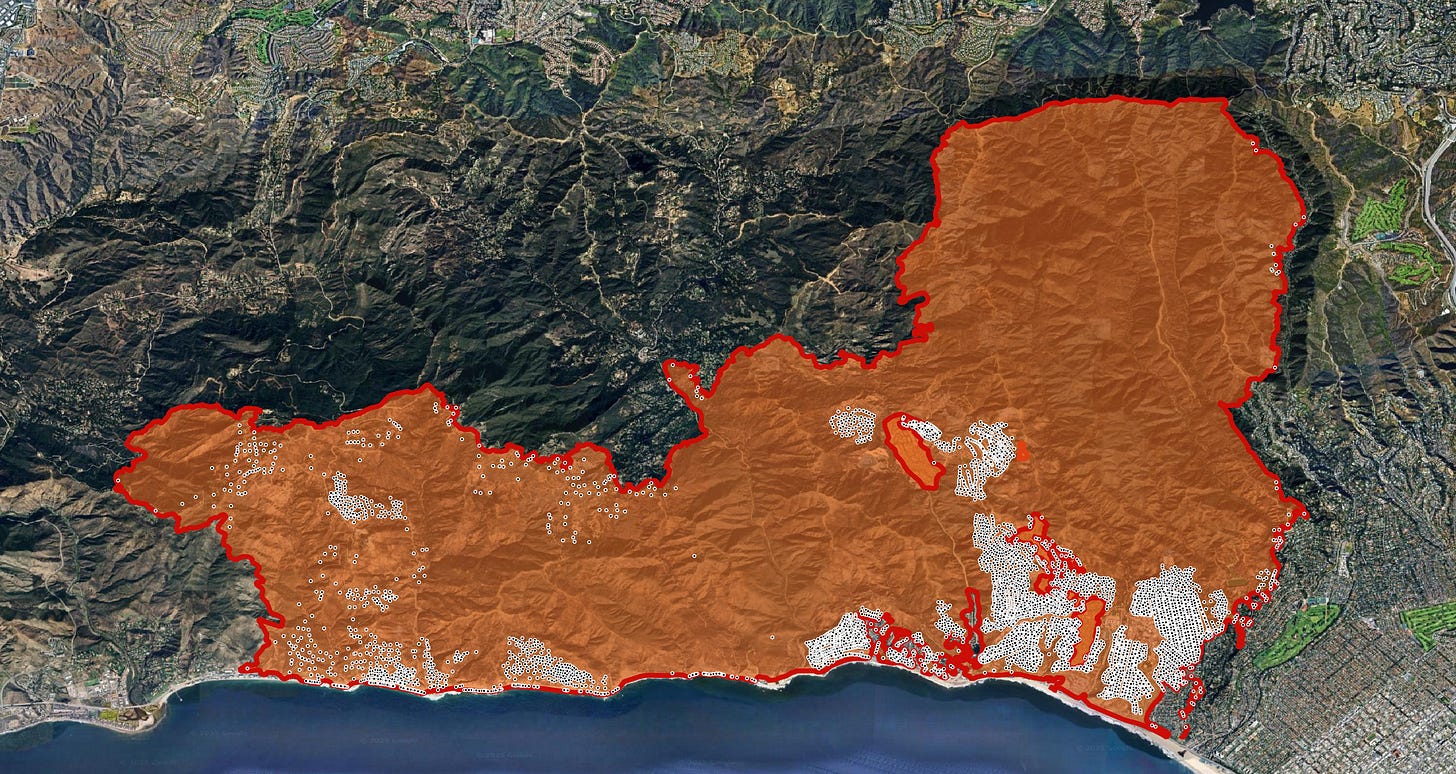

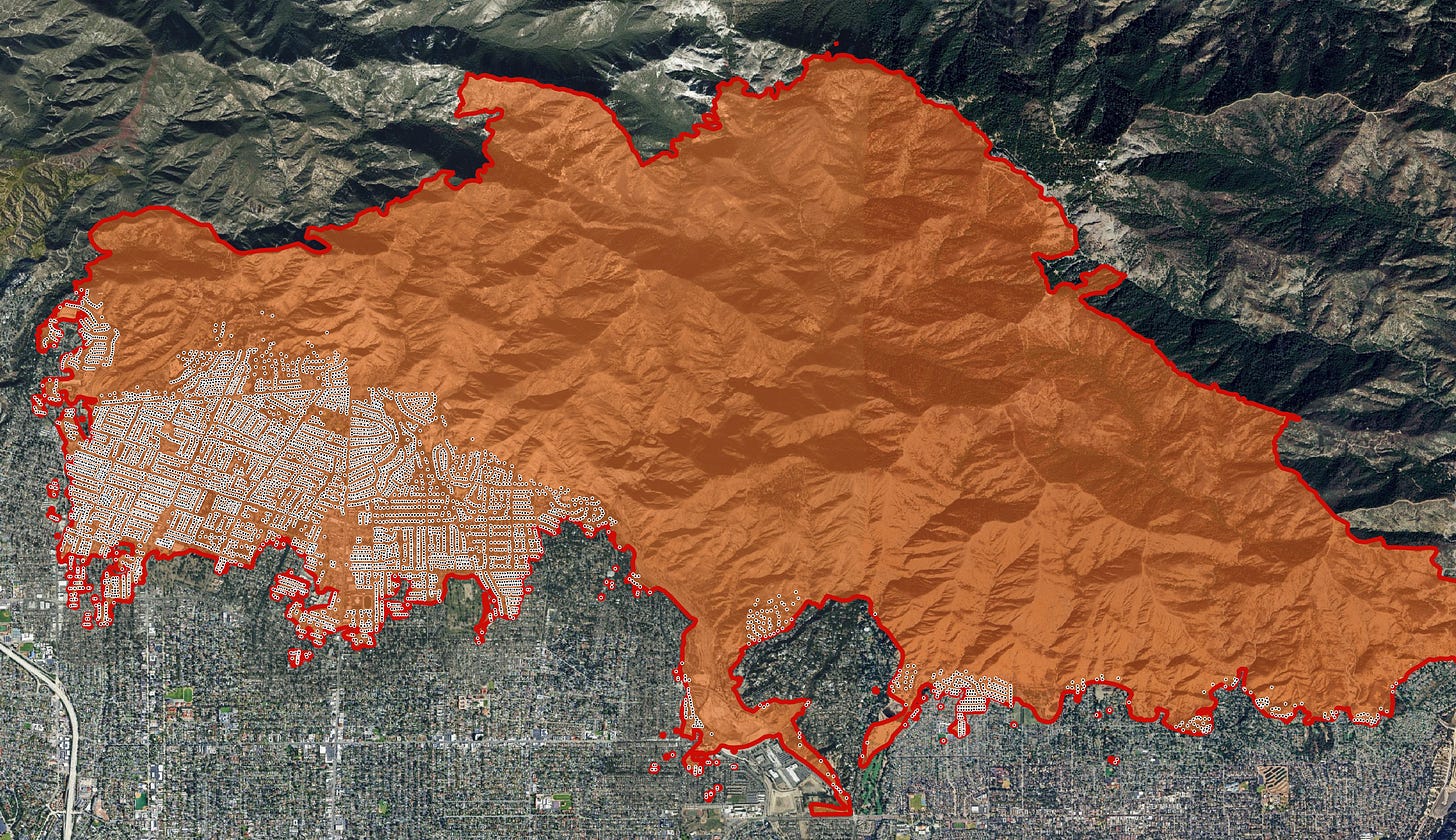

I pulled the fire perimeter dataset and spatially joined it with the assessed value dataset to see which properties stand within the fire perimeters.

Not all properties within the fire perimeter were destroyed, but aerial imagery suggests the vast majority were.

Land values tend to be higher along the coast and decrease further inland. So let’s take a look at the Pasifix Palisaes Assessed Land Values, with white text displaying the assessed dollar value of a Parcel in millions of dollars.

🏚️ One Lot is Worth $200K. The Identical One Next Door? $2.4 Million.

The reason lies deep in California’s tax code. Thanks to Proposition 13, passed in 1978, property tax assessments can increase by no more than 2% per year, unless the property is sold. That means:

A homeowner who bought in 1985 might be paying taxes on a $150,000 assessed value. Their neighbor, who bought the same house last year, might be assessed at $1.5 million

Same house. Same risk. But very different numbers.

The burnt-down Altadena area is, of course, cheaper than the Palisades, but inconsistencies are still there: $20,000 lots are right next to the $700,000 lots.

First-order Damage Assessment

If we simply sum the total assessed value of all single-family lots within the fire perimeter, we get a figure of $19.1 billion — including $12.9 billion in improvements, which are likely to be mostly destroyed.

But given that the median market value is approximately 2.2 times higher than the assessed value, we can scale this number up to arrive at a first-order estimate of $28.4 billion in actual fire damage — and that’s just for the single-family segment. This number has to be further scaled up above 30 billion because the summary is calculated on 2022 assessments.

Caveat: this is a rough and naïve approximation, but it highlights just how much current reporting may be underestimating the true scale of loss.

Where assessment values are closer to the market value

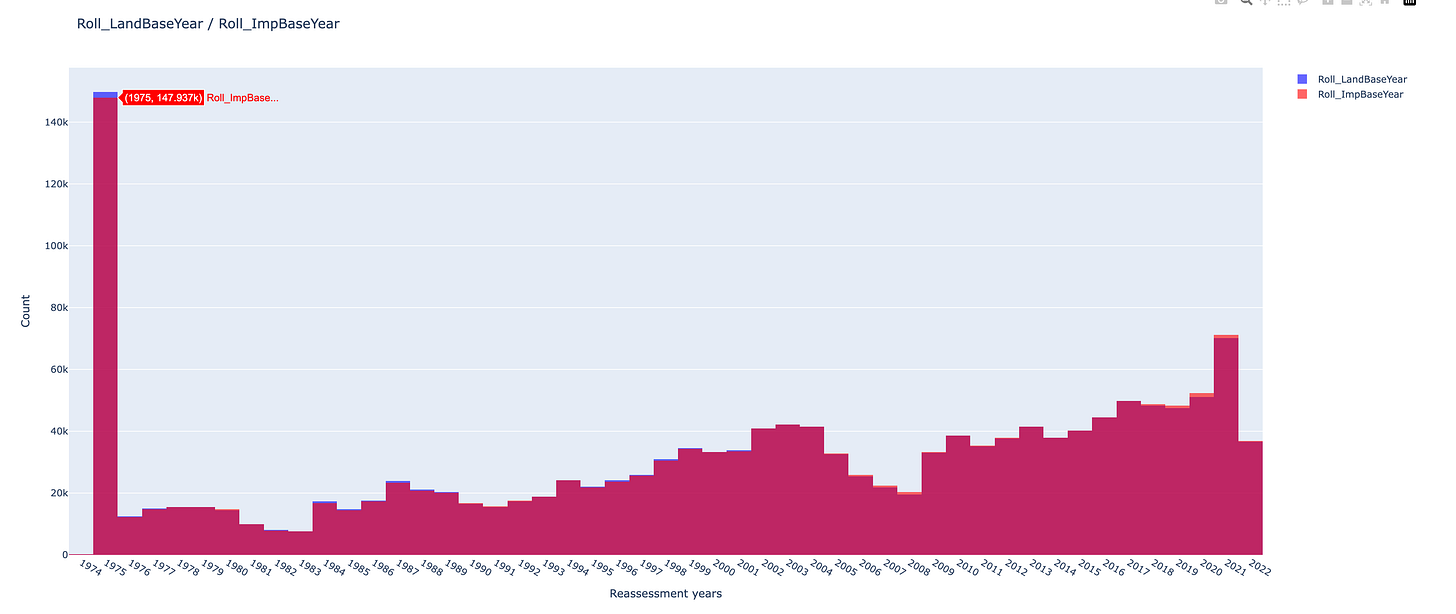

There are several property cohorts where the assessed value is close to the market value: recently built houses and recently sold.

Numbers for the newly built homes actually makes sense with $945.000 total assessed value:

The same applies to the properties with a more recent base assessment year. For properties with the base assessment year 2020 or later, the median is $745.000

The base year

In California, under Proposition 13 (1978), the base year is the year when a property was last reassessed at market value — typically:

- The year of purchase, or

The year of new construction or major improvement.

A histogram of base years reveals that a large share of properties in LA County are still anchored to legacy assessments — many dating back decades — meaning their assessed values remain significantly below market levels.

Conclusion

Because of how California's tax system works, assessed property values often reflect the past, not the present. As a result, when we tally up the cost of the fires using tax records, we’re massively undercounting the real financial damage.

This matters. It affects:

Insurance planning — if official values are too low, coverage may fall short.

Disaster funding — federal and state relief programs often rely on local damage estimates.

Risk modeling and resilience investments — cities can’t protect what they can’t properly measure.